Growing Pains

A Tale of Two Brokers in Three Acts

When growth is the goal, there’s no melodrama involved. Your role: to analyze all the options—all the time.

Cast

Kent Wynn, an insurance-brokerage CEO facing a slippery slope.

Justin Case, an ambitious manager at Kent’s firm.

Rich Lee, an insurance-brokerage CEO with a happier outlook.

Hugh Proffit, an investment banker specializing in the insurance industry.

Act I

Scene 1. The time: Much too late at night. The place: A sleek midtown office building. The setting: The handsomely appointed office of Kent Wynn. In a pool of light created by a designer desk lamp, Kent sits hunched over a pile of spreadsheets.

Kent (muttering between clenched teeth): Why isn’t share value increasing? This is supposed to be a great market for brokerages, but I’m seeing only a 6 percent increase in value per share over last year’s numbers. What happened to the 10 percent I expected?

He checks some numbers on his computer screen and looks at his spreadsheets again.

Kent (still talking to himself): What makes it even more frustrating is that we had a good year! Our top line grew from $8.54 million to more than $10.15 million! That’s [he does a quick calculation] an 18.9 percent increase!

Kent goes back to the reports on his desk. Yes, he’d done everything right. His managers had improved their sales planning. On the advice of his banker, Guy Wiley, Kent had completed the acquisition of a small brokerage with $1.1 million in revenue. And he was continually trying to benchmark his operations against those of firms in the top quartile of the industry. What was he doing wrong?

A knock on the open door. It’s Justin Case, one of Kent’s top managers. Justin has been working late, too.

Justin (smiling the smile of a producer who just landed another account): Hey, Kent—earning lots of money for us tonight? (Laughs merrily and exits.)

Kent smiles weakly at Justin’s retreating figure. Last year, Justin and the other top producer / managers had bought 20 percent of the firm’s holdings. Kent hoped they’d continue to buy an additional 10 percent each year for the next five years. That way, he could perpetuate the firm internally. But he needed at least 10 percent growth—preferably 12 percent—to entice them to keep buying.

As Kent swivels in his Aeron chair, he remembers something else: These same producers had agreed to accept shares in the firm in return for signing new employment agreements. The agreements were the stick—they included noncompete provisions and lowered commission splits. The shares with their promise of 10 percent growth in value per year was the carrot.

Now Kent spots something on his desk amid the pile of reports. It’s a business card from his old friend and fellow broker Rich Lee. The two men had met in a networking group that Kent’s financial advisor, Guy Wiley, had put together. Funny thing, though—Rich had abruptly fired that advisor and hired a new one, Hugh Proffit. Now Kent hears that Rich’s agency is thriving.

Kent taps the business card on his desk, lost in thought. Maybe it’s time to give his buddy Rich a call.

Scene 2. The same office, the following morning. Rich can be heard on the speakerphone.

Rich: …great, just great! And I’m telling you, it’s all because of the advice I’ve gotten from Hugh Proffit. That other guy, Guy, was always pressuring me to sell the agency and not once did he even take the time to understand my goals, my dreams and those of my staff in regard to our firm. My goal has always been to remain independent and create a viable plan to transition the ownership of my firm. To reach this goal I knew I have to continuously grow the firm. And even though I was benchmarking—just like you say you’ve been doing—I wasn’t seeing the growth I was looking for. When Hugh met with me, he explained that I needed to start doing things differently.

Kent: Differently? How?

Rich: For starters, to stop benchmarking just for the sake of achieving benchmarks and being a quote un quote top broker. Instead, he worked with me to outline my goals for my firm and then showed how achieving those goals tied directly to a concise, measurable goal of growing the per share value of our firm. The trick was to examine how every decision and initiative would impact value per share.

Kent: You know, that makes sense. If you grow the value of the firm you can do so much more. Your senior managers will want to buy your stock, you will have more cash, and you can attract many more professionals into the operation.

Rich But be careful, Kent. Growing the value of your firm and growing the value of each share of stock are often two different things. If you make poor decisions or acquisitions that aren’t properly analyzed and structured, you can quickly find yourself with an agency that might be worth more in total but with a much smaller increase in value per share and in some cases a decline in the value per share.

Kent (slowly and tentatively): That sounds familiar. We made an acquisition, grew our revenues by 19% but our per share value increased by only 6%, and I still can’t figure out why.

Rich: I’ve got an idea. Why don’t you come over here next week and meet with Hugh and me? I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised.

Act II

Scene 1. Rich Lee’s office in a neighboring city. As the curtain rises, Rich is sitting at an oval conference table and chatting comfortably with Hugh Proffit. They look up as Kent Wynn bustles in.

Kent: Sorry I’m late. You must be Hugh—Rich has told me a lot about you.

He stretches out his hand. Hugh rises to shake it.

Rich: Kent, before we start talking about your situation, I thought you’d be interested in seeing what Hugh did for me when we got started.

Hugh (smiling): You know, when I met Rich, he thought he knew what I was going tell him. “Acquisitions, acquisitions, acquisitions!” After all, isn’t that how investment bankers like me earn our living? (He shares a look with Rich. Both men laugh heartily.)

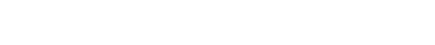

Rich: Then Hugh showed me something that really changed my mind. May I? (Rich goes to a bookshelf and retrieves a file. He brings it the conference table and opens it.) Hugh created this very simple table for me. And it wasn’t what I’d expected at all.

On the rear wall of the stage, a table is projected so that the audience can clearly read every line.

Rich: Take a look at the far-right column. See what I mean? It turns out that acquisitions are neither the key nor the best course of action. That strategy was projected to grow value per share by only 8.6% a year – yet acquisitions were clearly the riskiest of all the various options. In fact, all but one of the other initiatives could produce better results.

Kent (a look of comprehension slowly dawning on his face): So what you’re saying is…

Hugh: …that effective growth means focusing on multiple strategic initiatives simultaneously.

Rich: Once I understood that, I was able to communicate it to my managers and producers. And once they understood it, they became motivated to follow through. They realized that growing the company requires the same commitment to planning and execution as they had been spending on their individual sales strategies.

Kent: I’m impressed. Definitely. But…how did you do it? And how do you know it will work for me?

Hugh: The answers are both simple and sophisticated. Simple because planning and executing for growth in per-share value is really an iterative process. Sophisticated because it took me years to develop the kind of analysis required to create a financial model and then tailor it to your operation on a department-by-department basis.

Kent (interrupting): Department by department—you mean, like benefits, property & casualty, surety, retirement services? Why?

Hugh: Yes to your first question. As for why, the best way to demonstrate would be to me use your own numbers. Why don’t you send me what you have? Then let’s get together at your office next week to talk it over.

Kent: You’re on. In the meantime, memo to self: fire Guy Wiley!

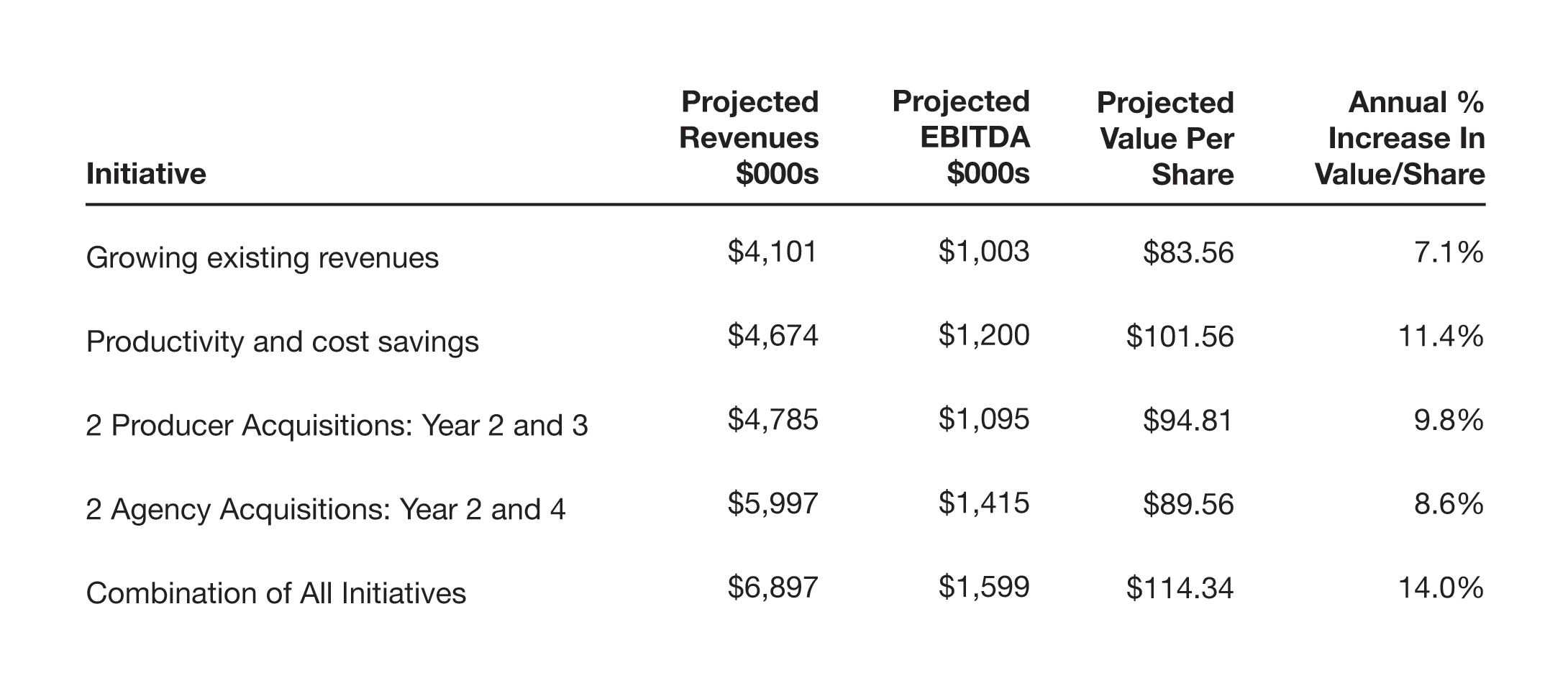

Scene 2. Kent’s office. Hugh and Kent are seated at a small work table covered with papers. On the rear wall of the stage, a table is projected so that the audience can clearly read every line.

Hugh: Okay, the first thing we see here is that the relative productivity of each of your departments is radically different. Producers in your benefits department are handling books of $721,000. And benefits AEs —which we define as all client service staff including marketing and claims support—generate revenues per employee of $309,000. But industry averages are closer to $1.1 million and $380,000, respectively. And the numbers for top firms are more like $1.3 million and $500,000.

He pauses to let Kent take this in.

Now, in the P&C division, the picture is different. The average producer is handling $1.3 million and the average AE $333,000. The top-performing firms handle $1.5 million and $380,000, respectively.

Kent: So we’ve clearly got a problem in benefits, and our P&C division is performing pretty well. I get it: we have to fix the benefits department.

Hugh: That would be a good start. But it isn’t the whole story. Think about it for a moment. What will you need to do to grow revenues in your P&C division by 10 percent?

Kent (looking a little confused): Ummm—get each producer to increase his book by 10 percent?

Hugh: Unfortunately, it isn’t that simple. At 10 percent, assuming you make no new hires, each P&C producer would have to manage $1.47 million in commissions next year, $1.61 million two years from now and more than $1.77 million in three years! Similarly each AE would have to handle $443,000 in commissions in three years from now. A very aggressive assumption, is it?

Kent (looking chagrined): Yeah, I guess you’re right. To reach the goal, we’d have to hire new people.

Hugh: And a lot of them. If all you wanted was to maintain your current levels of productivity, you’d need at least one more validated producer and three more AEs over the next three years. That’s a tough call for any firm.

Kent looks worried.

Hugh: Rich was in the same situation. He realized he would need to look at a more realistic level of growth—more like 6 percent a year. And he needed to get to work, pronto, on recruiting, hiring, and training new producers and AEs. The alternative is a situation where additional growth just isn’t feasible.

Kent: But what about industry benchmarks? That’s what my previous advisor always talked about. In fact Guy Wiley said the key to increasing value is to be at the top of the industry averages. Even his competitor, Rick Chase, says this – they can’t be wrong, or can they?

Hugh: Well let me ask you this. Have either Guy Wiley or Rick Chase even shown a statistically significant correlation between being at the proverbial peak of industry benchmarks and being the most valuable agency?

Kent: (after pausing a minute to consider the question) Now that you bring that up, no.

Hugh: Remember, benchmarks can help you identify opportunities for future growth—and also barriers to growth. But to really understand and plan for growth, you need to put those opportunities and barriers into the context of a financial model that shows you how to take advantage of the opportunities and work around the barriers to put your firm and its value in a better place tomorrow, next month and next year. You need to remember three important words: analyze, plan, and execute.

Kent: Can you do that for me?

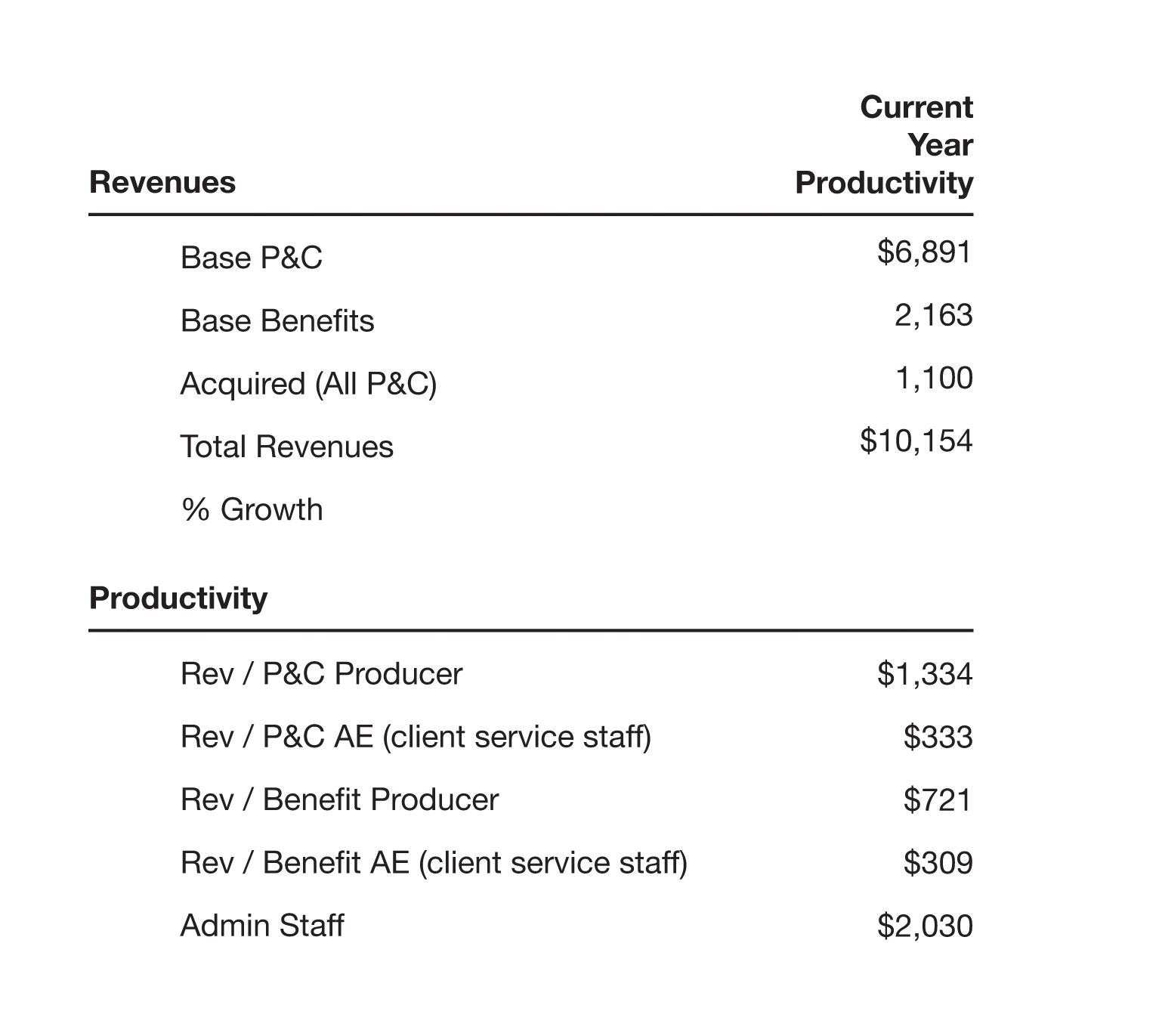

Hugh (smiling): As a matter of fact, I’ve taken the liberty of creating a baseline forecast for your firm assuming 6% not 10% annual growth in existing revenues and employee productivity growing at the industry average of approximately 2.5% per year. Let’s take a look.

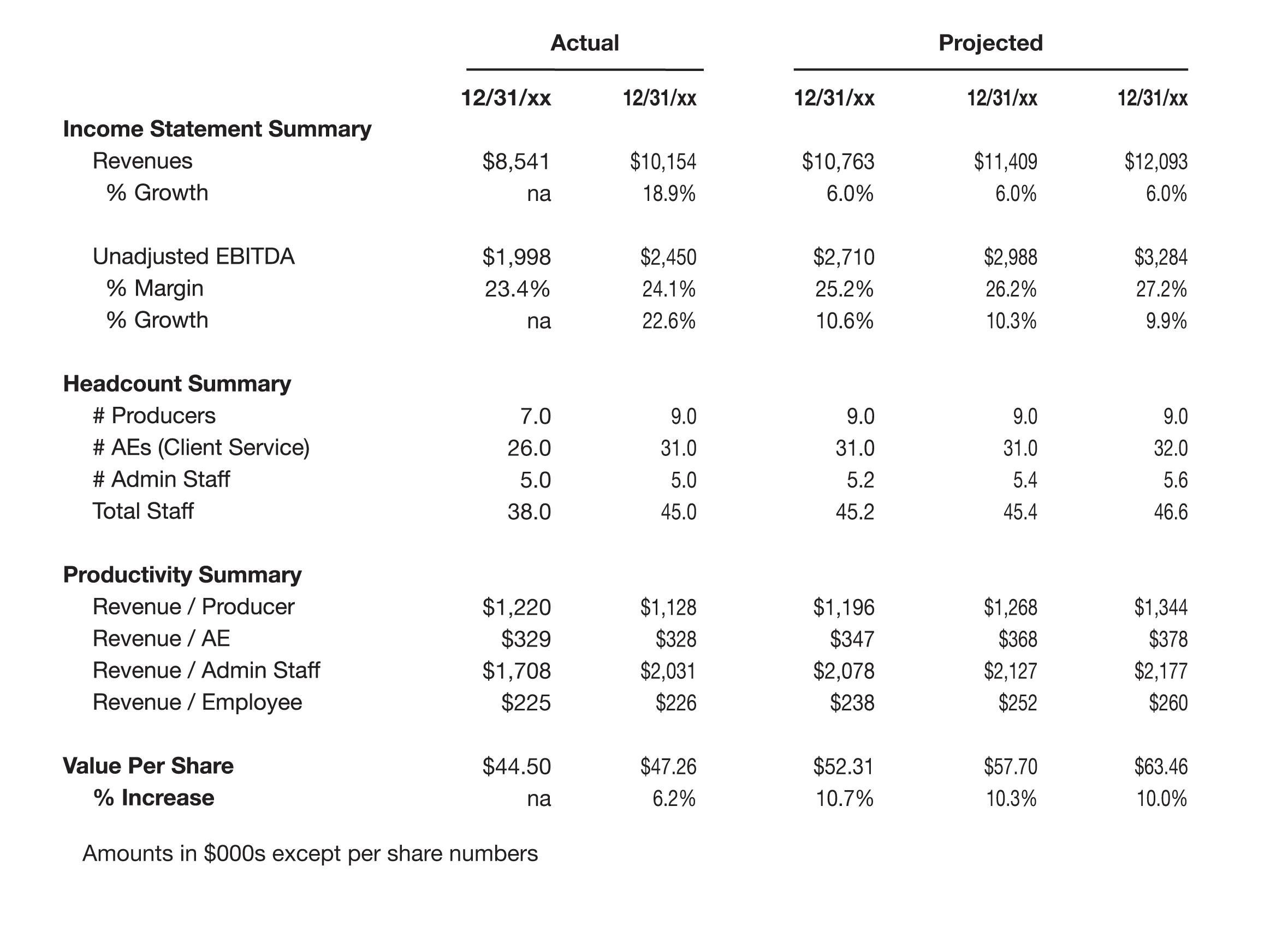

A new projection fills the rear wall.

Forecast for Kent Wynn & Co.

Topline Initiatives for 6% Annual Revenue Growth

Kent: Wow. Not very inspiring, is it? If I’m reading this correctly, we’re seeing an increase in value per share of only 5.7 percent per year over the next three years.

Hugh: I’m sorry to say that’s true. But remember: this forecast doesn’t reflect any actions you might take to improve productivity. For a firm like yours, we’d like to see productivity growth—that is, increased revenues per employee—between 5 percent and 7 percent per year.

Kent: That’s pretty aggressive!

Hugh: Perhaps. But consider this: Even when their operating margins improve modestly or not at all, the top brokers achieve per-employee revenue increases of about 3 percent per year. So to achieve a 6 percent increase, you’d be improving your employees’ overall productivity level by only 3 percent per year relative to your industry peers.

Kent: Three percent, eh? We could do that!

Hugh: And if you do, take a look at what happens. Instead of growing by only 5.7 percent, your value per share increases by more than 10.0 percent per year for each of the next three years!

A new chart is projected onto the rear wall.

Revised Forecast for Kent Wynn & Co.

Incorporating Productivity Initiatives into the Plan

Hugh: Of course, internal initiatives such as restructuring work flow or altering compensation plans to encourage growth are only part of the story. You also need to look at growth opportunities that come from outside.

Kent: If you’re talking about acquisitions, we’ve made good progress there. I told you about that acquisition just over a year ago with $1.1 million in revenue. As a result, our revenues grew by 19 percent, EBITDA increased by 23 percent, and total company value increased by 15 percent.

Hugh (prompting): And your value per share?

Kent (looking slightly embarrassed): Yeah, you got me there. We issued shares in our company to the seller, which increased the total number of shares outstanding. And that’s why value per share increased by only 6 percent.

Hugh: Let’s take a look at that deal to see whether it might have had a different outcome. As I recall, you paid 2.25 times the $1.1 million in acquired revenues, for a total purchase price of $2.475 million.

Kent: Correct. We paid $1.114 million in cash at the close and the remaining $1.361 million in stock—30,590 new shares, using our latest valuation to establish the price per share. Guy Wiley thought this was a good deal.

Hugh: But what multiple of EBITDA did you pay?

Kent: The same multiple as our own valuation—8.00. Guy Wiley showed us how the acquisition would produce a pro forma EBITDA of $308,000, or a 28 percent margin.

Hugh: Seemed reasonable, didn’t it? But let’s put aside the context of the market. Let’s take a peek at the deal in terms of how it affects you and your operation assuming you grow productivity at 2.5% per year. Suppose you didn’t do the deal at all?

Kent: What do you mean?

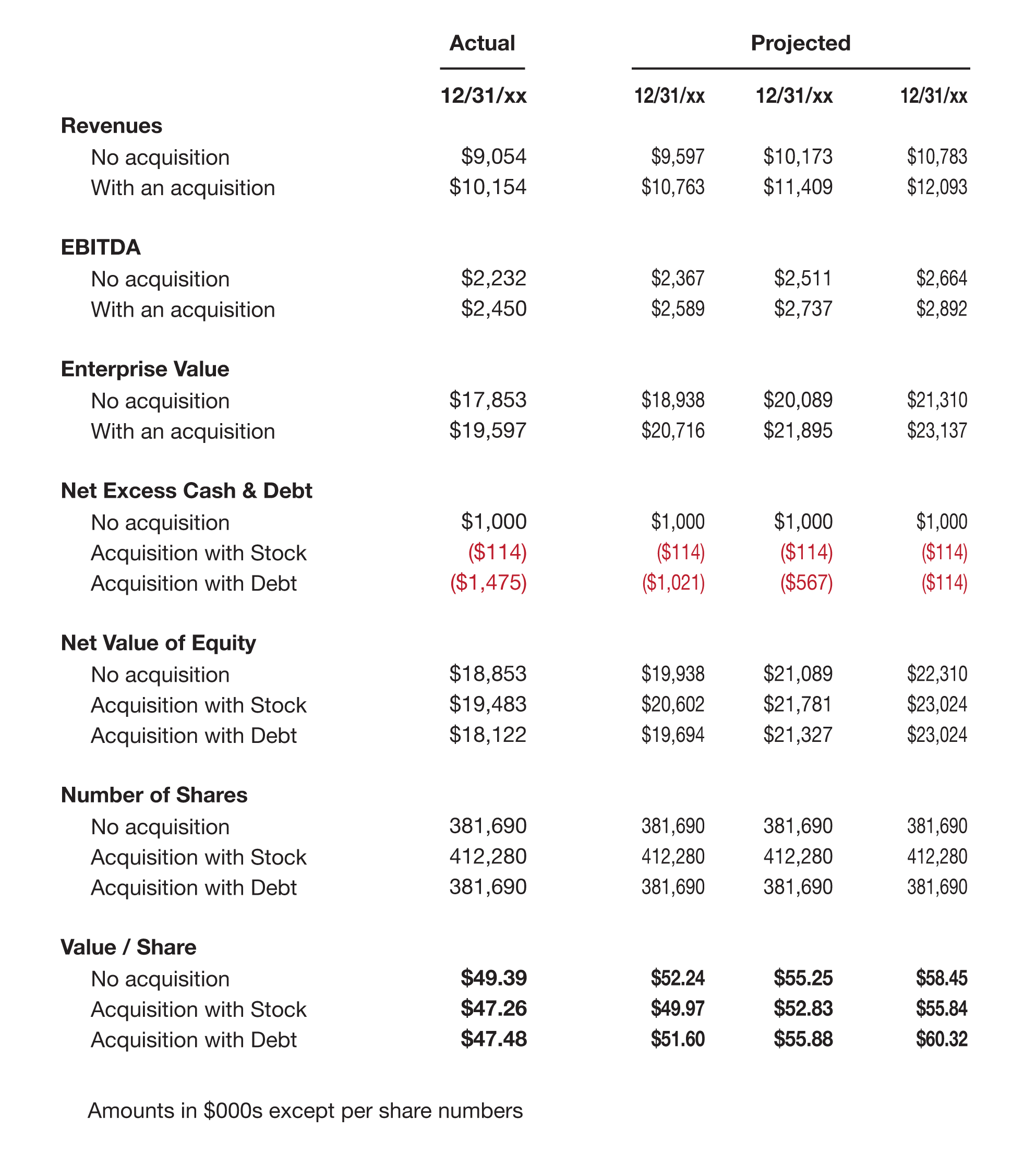

A new table appears projected on the rear wall.

To Deal or Not to Deal?

Kent: Holy Moley! You mean to tell me that I actually lost value per share on the acquisition? Then why do so many firms acquire brokers in order to grow? Surely so many people can’t be all wrong…can they?

Hugh: I won’t attempt to answer that! But I will tell you a couple of things about that deal. First, the price was inflated at 2.25 times revenues. Second, you’d have been better off using debt instead of equity to finance the purchase.

Kent: But would taking on debt make me an under-performing agency? One of the key benchmarks so many advisors keep telling me is to minimize my debt if you want to be one of the best ranked firms in their universe.

Hugh: Well if that’s true one would have to surmise that all the public brokers and almost every successful American company is an under performing company yet we all know these public brokers continue to grow and expand! In fact, just look at your own deal assuming you had taken on debt – even at your inflated price. Under this type of deal, your value per share would grow to $60.32 in three years instead of the $55.84 as shown under the structure suggested so strongly by your advisor and his abhorrence to debt. In fact, to justify the price suggested by your advisor, you’d need to run an EBITDA margin closer to 33 percent than 28 percent. Assuming you’re more likely to margin any operation at your company average of 24 percent, a 1.9 times purchase is really an 8 times EBITDA multiple. Bottom line: you overpaid. And if you had paid closer to 1.6 times revenue—a 6.7 multiple—your current per-share value would be much closer to $49 than your current $47.

Kent: I get the picture. From now on, I need to do this sort of analysis.

Hugh: Or find someone else to do it for you.

Kent: Like you, for example?

Hugh: Like me, for example. Remember, this is just a summary analysis. The actual work is much more complex. It involves forecasting your operating-income statements, integrating them with income accruing from acquisitions of firms and producers, and integrating all of that into a consolidated set of cash-flow and balance sheets—not to mention accurately tracking changes in your capital and equity structure. If your staff has the time, experience, and skill to do these projections, then by all means—go ahead!

Kent (looking sheepish): I hear you. I’d rather have them producing revenue for me. So…what’s next?

Act III

Scene 1. One year later. Kent, Rich, and Hugh are finishing lunch at a trendy new midtown restaurant.

Kent (smiling broadly): I’d like to propose a toast.

Rich (teasingly): Got something to celebrate, Kent?

Kent: Sure do. What a difference a year makes! Thanks to Hugh Proffit, I’ve turned my firm around. I’ve hired another producer and two CSRs, and I’m actively recruiting more. My managers are more motivated to follow through on all their growth initiatives because they know it means a higher value for their shares. And we’re preparing for another acquisition—with much better terms than the last one, I might add.

Rich: I’ll drink to that!

Hugh: Kent, I’m delighted for you. But, you know, there was nothing magical about what I did. It all comes down to three simple words…

Rich and Kent (chorusing): Analyze, plan, and execute!

Hugh (beaming): What good students you are.

Kent: And one other thing: Hire an advisor who knows that growing value per share isn’t a matter of chance—it’s all about hard work and staying focused on all the initiatives.

Hugh and Rich: Hear, hear!

Curtain.